Why Congress Can’t Seem to Fix This 30-Year-Old Law Governing Your Electronic Data

Why Congress Can’t Seem to Fix This 30-Year-Old Law Governing Your Electronic Data

New questions about the FBI’s power to access data have shifted the years-long political debate over reform of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act.

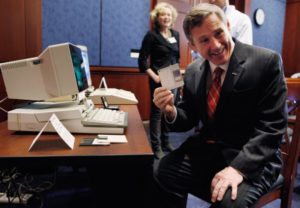

Lawmakers including former U.S. Senator Mark Kirk, seen here holding up a floppy disk in 2011, have been calling for reforms to the Electronic Communications Privacy Act for years.

Lawmakers including former U.S. Senator Mark Kirk, seen here holding up a floppy disk in 2011, have been calling for reforms to the Electronic Communications Privacy Act for years.

You may not know it, but there is a 30-year-old law that federal investigators can use to access your stored electronic content. It went into effect long before you probably sent your first e-mail, much less a text on your phone.

Will this be the year that Congress finally updates it? There is more pressure than ever to change the law after years of failed attempts, and the House of Representatives passed a reform last week. Whichever way the debate plays out in Washington, though, the Trump administration will probably prefer updates that strengthen the FBI’s powers over those that weaken them.

In 1986, the writers of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, or ECPA, could not have anticipated the widespread popularity of today’s cheap and free cloud services, or the degree to which people would be storing information about their lives on data servers they do not own. Civil liberties advocates argue that the law’s language gives the FBI too much power. Investigators need only a subpoena, not a warrant approved by a judge, to get an individual’s e-mails or other electronic messages stored in the cloud, as long as they are more than six months old.

Recommended for You

Recommended for You

Nonetheless, bipartisan efforts in Congress to update ECPA have repeatedly stalled despite strong support from civil liberties groups and dozens of technology companies, including Google, Facebook, and Microsoft. Last April, the House of Representatives voted 419-0 to change the law so that a warrant would be required to access all stored content, but the Senate version of the bill died in the Judiciary Committee. Jeff Sessions (now the attorney general) and some of his Republican colleagues on the committee led the opposition.

Last week, the House passed the bill again. Will it stall like all the previous ones? The president has not taken a public stance on the issue. No one knows when or whether the Senate will take up its own version of House’s legislation, and it is hard to say whether it will face the same sort of resistance in the Senate that it did last year.

But a new issue has arisen that might make reform more likely this time around. In July, a federal appeals court ruled against the Department of Justice, finding that a warrant issued under the ECPA could not compel Microsoft to disclose data it was storing outside the U.S.—in Ireland, in this case (see “Microsoft’s Top Lawyer Becomes a Civil Rights Crusader”).

That means DOJ may want Congress to come up with “some sort of fix that extends the reach of the warrant authority, at least in some circumstances, to data that’s held overseas,” says Jennifer Daskal, a professor of law at American University and former counsel to the assistant attorney general for national security. Though a federal magistrate judge disagreed with the Microsoft/Ireland decision earlier this month, “the law is in flux,” says Daskal.

Daskal says Congress should also change ECPA to make it less difficult for foreign governments to access data held in the U.S. that pertains their own citizens. The law blocks U.S. companies from disclosing stored content to foreign governments. To get content for an investigation, foreign investigators must go through the U.S. government and complete a time-consuming mutual legal assistance process.

To overcome this inconvenience, some countries have passed laws mandating that companies store copies of their data locally. The U.K. and Brazil have each passed aggressive surveillance laws in which they claim the authority to make companies disclose content stored in other countries. Without a change to ECPA, more countries will be tempted to pass similar laws, which could lead to a fragmentation of the global Internet. Foreign governments could also use malware and other “surreptitious means” to access the data they seek, says Daskal.

Any ECPA reforms could be considered individually or as a comprehensive package. Or they could potentially be attached to other bills, like the reauthorization of certain provisions in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), which also must happen this year. And of course, it’s Washington, so there is still the possibility that nothing happens at all.

Leave a Reply